Boneyard Beach

There are moments when you are looking for something very specific, and then end up finding something completely different. That’s how I felt last year in the USA, when I really wanted to photograph one of the Oak Alleys that are so typical for the southern states – and finally found myself standing on a beach full of dead trees.

Boneyard Beach

Before I flew to South Carolina last September, I talked to my friend Phil about my photo plans. He picked out a number of such alleys within reasonable distance. My favorite one was quickly chosen: Edisto Island, more precisely, Botany Bay Plantation.

The access road to the plantation is a green tunnel. On both sides of the gravel road, the oaks grow in close proximity and stretch their branches across the path. The lush vegetation in the marshy terrain next to the road further enhances the effect.

This tunnel effect doesn’t come fully across on the photo – what fortunately doesn’t come across either are the hundreds of mosquitoes that plagued me in the few minutes outside the car. Well, if you want to have nice photos, you have to sacrifice something…

If you have to drive an hour to get to such a place, then of course you don’t leave it at just looking at the access road. These days, Botany Bay Plantation is an extensive nature and wildlife preserve that has a few special features to offer. The most striking one is certainly ‘Boneyard Beach’.

On this beach of Edisto Island, the sea gradually removes the sand – a process that was accelerated even more by a hurricane some years ago. Where the land is pushed back, the trees are left standing in the salty surf and die. What remains are abstract skeletons that give the landscape an unreal and eerie impression.

Exposure

When Phil, his wife, and I arrived at Boneyard Beach, it was high tide, and the full moon made it especially high. A storm off the coast caused a lot of movement in the water. On the one hand, the waves reached up to the dense vegetation in many places, so that you couldn’t walk far. On the other hand, the tree skeletons stood deep in the water – exactly what you want for a photo.

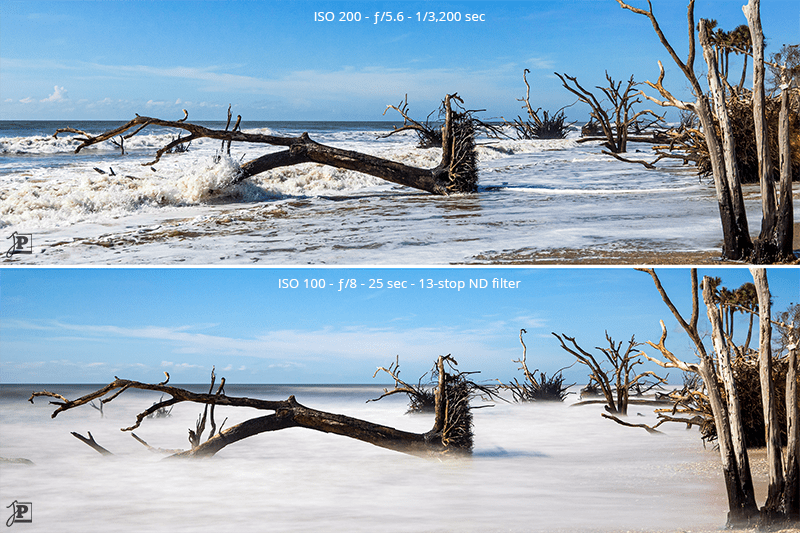

But how do you capture such a scenery? My personal philosophy when it comes to photographing water in motion is that you pick one of two extremes: Either you choose a very hast shutter speed to freeze the movement and show the wildness of the water. Or you expose for a very long time to literally let the movements flow into each other.

The first variant was no problem. The blazing midday sun that day provided more than enough light to work with exposure times of 1/3.200 or 1/4.000 seconds. This was a great way to capture the moment when a wave breaks on a log or rootstock and the water splashes in all directions.

But for the planned long exposures exactly this was a problem. I had two gray filters with me: One that darkens the image by three f-stops, thus increasing the exposure time by a factor of eight (ND8), and a second one that even makes it possible or necessary to take exposures a thousand times longer than usual (ND1,000). But if you start at 1/3,200 seconds, even ND1,000 only gives you one third of a second of exposure time – not enough for the image I had in mind. So I screwed the two filters on top of each other and also adjusted the settings for aperture and ISO so that I finally got shutter speeds of 20 to 25 seconds.

The effect of these opposing exposure times can be seen in the direct comparison:

The waves give an idea of how windy it was there. So I was glad that I had brought my sturdy tripod and not just the small travel one, because for long exposures, steady support for the camera is indispensable. The salty spray stressed my equipment a lot that day, and back home I had to thoroughly clean everything. But: the effort was worth it!

The result

An exposure time of 20 seconds turns the surf into fog – which in my eyes enhances the mystical effect of Boneyard Beach.

The picture can be found as a June sheet in my 2019 calendar.